See our information on Food for more on diet and Crohn’s.

Hydration

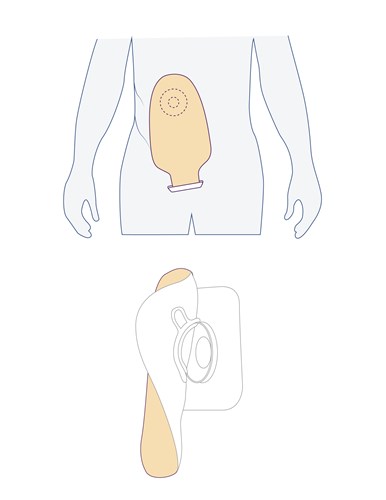

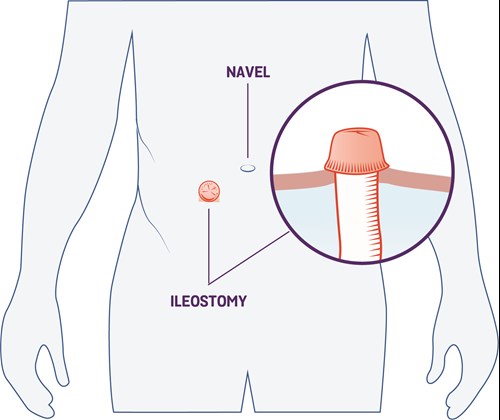

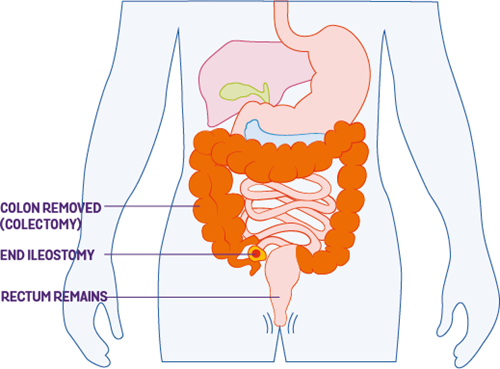

Your colon (part of your large bowel) is important for absorbing water. If you have your colon taken out you have a higher risk of dehydration. You may find it helps to drink fluids and rehydration drinks, including electrolyte mix. Our information on Dehydration has more on staying hydrated after surgery.

Work and finances

If you work, you may be wondering how surgery will affect your job and your income. It can take from 2 to 10 weeks before people feel able to return to work. This depends on the type of surgery you’re having and the type of job you have. If you work in a very physical job, you may need more time off.

If you can, it’s best to let your employer know early on about your medical needs and time off so they can make adjustments. It may help to read our information on employment.

If you are absent for more than a week, you will need to get a ‘fit note’ (‘statement of fitness for work’) from the healthcare professional who is caring for you. They can make suggestions for additional support or adjustments when returning to work. This could include building up slowly to your normal hours and duties. This is called a ‘phased’ return to work.

See the ACAS website for more information on returning to work after an absence.

If you’re worried about money, have a look at our information on finance and benefits. You may be eligible for support. You can also visit the UK Government website or Citizens Advice for more information on welfare benefits. If you care for a child who lives with Crohn’s, you may want to read our information on disability benefits for children to see you if are eligible for financial help.

School and university

You may need to take some time out of studying to recover from surgery. Try to speak to your school, college or university as early as you can so they are aware of the situation. They may be able to give you extended deadlines or adjustments for exams. See CICRA for more information on Crohn’s and schools.

Emotional reactions

Everyone reacts to surgery in their own way. And your emotions may even change during the process. You may feel worried or scared, maybe nervous. You may feel a sense of relief. Or you may feel doubt about whether having surgery was the right decision. Going through lots of different emotions can be exhausting. Emergency surgery can be especially difficult as there is less time to adjust. The people close to you may also find it difficult to cope with the thought of you having surgery.

You may find it helpful to talk to someone about these feelings. IBD nurses, stoma nurses and psychologists can support you. You can also speak to your GP about local psychology services. Our information on mental health and wellbeing has further details about this.

It may be helpful to talk to other people who have had surgery for their Crohn’s or who have a stoma. Check our support for you page for ways you can connect to others living with Crohn’s or Colitis.

Body image

Your body may look different after surgery and you may find this difficult to come to terms with. On the other hand, you may feel that having surgery improves your body confidence. You may feel better and able to do the things you enjoy. Maybe you can start going to the gym. Or maybe you have the energy to be intimate with a partner again. If you’re having worries, talk to your IBD team. Your nurses will likely have spoken to lots of people about their body image worries. It may also be helpful to speak to others – friends, family, or other people who have been through a similar experience. Check our support for you page for ways you can connect to others living with Crohn’s or Colitis. Our information on mental wellbeing may also be helpful.

Sex and relationships

You may be worried about how surgery will affect your sex life. Your surgical team can give you specific advice about when they think it’s safe for you to have sex after surgery. Going back to sexual activity may mean exploring other ways of being intimate or new positions. It can be difficult to talk about sex, but being open about your needs and concerns can help.

Our Sex and relationships information has more on how surgery may affect sex and suggests other ways you could be intimate with a partner.

Fertility and pregnancy

If you’re thinking of having children it’s important to let your surgical team know. Anyone with female reproductive organs having surgery in the lower tummy area (pelvic area) may be at risk of reduced fertility. It’s thought that surgery in this area of your tummy can cause scar tissue (adhesions) around the fallopian tubes and ovaries. This can make it more difficult to get pregnant. Ask your surgeon whether your type of surgery may increase your risk. But if you do not have surgery, active Crohn’s disease may also make it more difficult to get pregnant.

For some people, it may be possible to delay surgery until they have completed their family. For other people, they may be able to have keyhole surgery. The risk of fertility problems is lower with this type of surgery.

You should still use contraception if you do not want to get pregnant, or do not want to make someone pregnant after surgery.

If you do become pregnant, either before or after surgery, your doctors will advise you on what options are safest for you and your baby. For example:

- If you have a stoma, it’s still possible to deliver vaginally, but you may need a caesarean section if any complications arise.

- Vaginal deliveries are not advised if you have active Crohn’s in the area around your bum (perianal Crohn’s).

Any surgery in the tummy, including a caesarean section, or surgery for your Crohn’s, can lead to scar tissue forming (adhesions). Adhesions can make any future surgery a bit more complicated. Your surgeon should be able to give you further advice on this.

You may find it helpful to read our information on Reproductive health and on Pregnancy and birth and postnatal care and breastfeeding.