Types of X-rays and imaging tests:

Abdominal X-rays

An X-ray is taken of your tummy (abdomen) to look for areas of swollen (distended) bowel above blockages and obstructions. X-rays can also be used to diagnose toxic megacolon. Toxic megacolon is a widening or swelling of the colon that may cause a rupture (perforation). These X-rays are often used in emergency cases. They do not show as much detail of the gut as some of the other imaging tests (see below).

This x-ray is very quick to perform.

Barium studies

Barium is a white, chalky fluid that is not absorbed into the body but instead forms a temporary coating on the inside of the gut. Since X-rays cannot pass through barium, it is used to provide a clearer outline of the gut on X-ray pictures.

You will be asked to take barium in different ways depending on the part of the gut that is being looked at.

Barium studies have become less common because CT and MRI imaging tests are more widely available (see below).

The different types of barium tests are:

Barium swallow and meal – the radiologist will ask you to drink a mixture of barium and water while they take X-ray images of the upper part of the gut, such as the oesophagus and stomach.

Barium follow-through - you will swallow a mixture of barium and water and be asked to take a laxative the day before the test. The radiologist will take X-ray images of your stomach and small bowel as the barium passes through your gut. You will be told what to eat and drink before and after the test.

Barium enema - an enema is used to pass barium directly into your bowel through a short tube placed in the bottom (anus). Your bowel must be empty of poo before the test to make sure the images are clear. You should have instructions on what to eat and if you need to take laxatives before the test.

After taking barium, your poo will turn pale and chalky looking for a few days.

Chest X-rays

Biologic medicines are common treatments for people with Crohn’s or Colitis. Because they suppress parts of the immune system, all biologics carry an increased risk of infections such as tuberculosis (TB). Before starting biologics, you will need to have a chest X-ray to check you don’t have a latent TB infection. A latent infection is when the TB bacteria is in your body but is not active and you don’t have any symptoms. People with latent TB are not infectious. This type of x-ray is very quick to perform.

DEXA (Dual Energy X-Ray Absorptiometry) scans

DEXA scanners use low dose X-rays to measure how dense (strong) your bones are, usually in the spine or thigh bone. This is a simple, painless test that takes around 10 minutes.

DEXA scans can show if your bones have become thinner and weaker than normal – a condition known as osteoporosis. People with Crohn’s or Colitis have an increased risk of developing osteoporosis. Having steroid treatment or low calcium levels can also increase the risk of weak bones. If you are taking steroids long-term, it is recommended that you have a DEXA scan every year. See our information on bones.

Computerised Tomography (CT) or Computerised Axial Tomography (CAT) scans

A CT scanner is a special machine that uses a series of X-ray beams to build up a detailed picture of the gut. During a CT scan, you usually lie on a moveable bed, which slowly passes through the centre of the scanner. The scanner is a ring that rotates around your body while it takes each scan. The scan is quick and painless.

You may be given a contrast dye before the scan, which helps show more detail of the gut on the scans taken. The contrast may be given in the form of a drink to swallow, an enema in your bottom or injected into a vein in your arm. You should get a letter telling you everything you need to know about the scan, including if you need to have a contrast dye.

Another type of CT scan is a CT enterography. This scan is used to look at your small bowel in more detail. Usually, you will have to drink a contrast dye before the scan, then during the scan another type of contrast dye will be injected into a vein in your arm. CT enterography scans help find inflammation, blockages and bleeding in the small bowel.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

MRI scans use strong magnets and radio waves to create images of the inside of the body. MRI scans do not use X-ray radiation. The MRI scanner looks like a long tube or tunnel. You will be asked to lie very still on a moveable table, which slides slowly inside this tunnel. An MRI will usually last around 20 to 30 minutes.

You may be given a contrast dye before the scan, which helps show more detail of the gut on the scans taken.

MR enterography (MRE) is a special type of MRI. This scan is used to look at your small bowel in more detail. Usually, you will have to drink a contrast dye before the scan, then during the scan another type of contrast dye will be injected into a vein in your arm. MR enterography scans help find inflammation, blockages and bleeding in the small bowel.

The MRI scan can be noisy and make tapping sounds. You may be given earplugs or headphones to wear. The radiographer is controlling the MRI scanner from another room, but they can still see and hear you to make sure everything is going okay. If you are scared of enclosed spaces (have claustrophobia), let the radiographer know that you are worried before the test. They can offer support and help you feel more comfortable.

If you feel really anxious about having an MRI scan, you may want to ask your GP or consultant for a mild sedative; this is a medicine to help you feel sleepy and relaxed. You should arrange this before your MRI appointment.

Because MRI scanners use magnets, they are not suitable for most people who have implanted metal or electronic device, such as a pacemaker or artificial joint. Please let your team know and they can check if your implant or device is compatible and suitable for an MRI scan.

You should get a letter telling you everything you need to know about the scan, including if you need to have contrast dye.

Another type of MRI is a Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography (MRCP). This scan shows detailed images of the liver, gall bladder, bile ducts, pancreas and pancreatic ducts. An MRCP can be used to diagnose Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis (PSC).

Ultrasound

Ultrasound is another type of scan that is used when diagnosing and treating Crohn’s or Colitis. Ultrasound scans use sound waves to create detailed images of the part of the body that the radiographer is moving the scanning probe or wand over. Ultrasound does not use X-ray radiation.

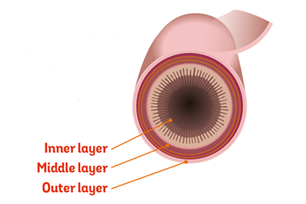

Ultrasound can show thickening of the bowel wall, abscesses and strictures.

Before the scan, you will need to drink large amounts of liquid and avoid eating for a few hours. You may be given a contrast dye before the scan, which helps show more detail of the gut on the scans taken.

You should get a letter telling you everything you need to know about the scan, including if you need to drink any contrast dye.

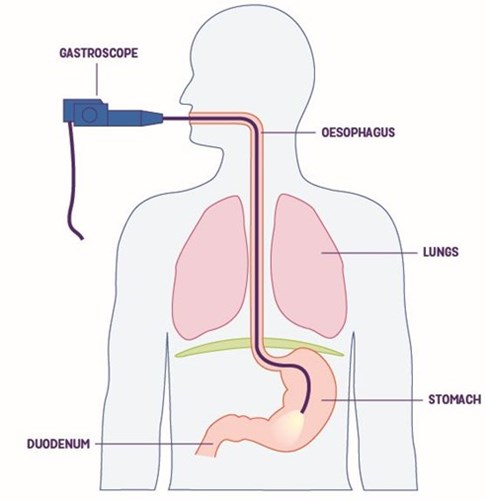

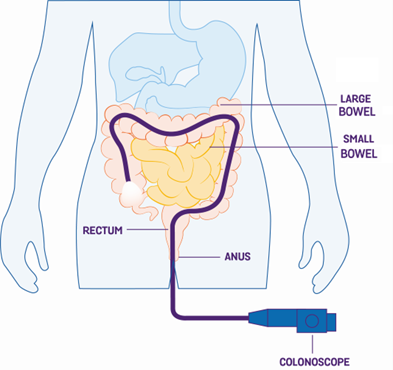

Endoscopic Ultrasound Scans (EUS) use a special endoscope with a tiny ultrasound transmitter in the tip. Like a normal endoscope, EUS is inserted through the mouth to examine the upper part of the gut or through the bottom (anus) to examine the colon (part of the large bowel) and ileum (the last part of the small bowel). Your doctor will be able to take small samples (biopsies) if they need to. You will usually be given a sedative or a local anaesthetic spray to numb your throat. Find out more in the section above on endoscopy.

SeHCAT Scan

A SeHCAT scan is used to find out whether diarrhoea is caused by bile acid malabsorption (BAM).

When you eat, bile salts (made in the liver and stored in the gall bladder) are released into the small bowel to help break down food. Normally, when bile salts reach the end of the small bowel, they are absorbed into your blood. Bile salts may not be absorbed if the ileum (last part of the small bowel) is inflamed due to Crohn’s or has been removed during surgery. Instead, bile salts enter the colon (part of the large bowel) along with high levels of water, leading to watery diarrhoea.

The SeHCAT scan involves two separate appointments. At your first appointment, you will be asked to swallow a small capsule containing a small amount of radioactive bile salts. After around an hour, a scan will be taken using a machine that can measure radioactivity. After seven days, a second scan will be done to measure the amount of radioactive bile salt still left in your body, showing whether you have problems absorbing bile salts.

There is no need to be concerned about the level of radiation since the radiation dose is low (equivalent to the amount received from natural sources of radiation in about two months). You will not need to stay away from anyone after the scan.

You should get an information sheet with your appointment letter from your hospital telling you everything you need to know about the scan.